|

The Political Risk of Emancipation |

In 1860, Lincoln had been elected with less than half the popular vote and no mandate for abolition. By 1863, when his Proclamation took effect, emancipation found increasing support among both the Northern public and Union soldiers. An Indiana colonel wrote that few soldiers were abolitionists, but they wanted “to destroy everything that in aught gives the rebels strength,” so “this army will sustain the emancipation proclamation and enforce it with the bayonet.”

Such acceptance was by no means universal. A New York newspaper editor told a mass meeting that “when the President called upon them to go and carry on a war for the nigger, he would be d___d if he believed they would go.” Draft riots there in July 1863 constituted the worst mob violence in American history. Threatened with being conscripted to fight a war now bound up with emancipation, rioters targeted black people with beatings, lynchings and the destruction of property, including the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum. More than 100 people were killed.

|

|

|

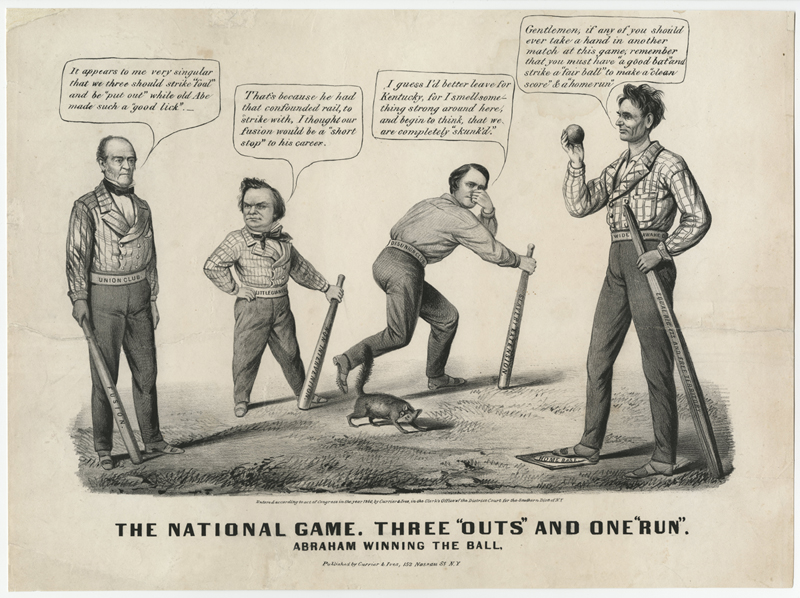

In 1860, Lincoln won in a four way race. Currier and Ives, 1860. |

Lincoln’s issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation posed a serious threat to his re-election in 1864. Henry J. Raymond, chairman of the Republican National Committee, told the president:

The tide is setting strongly against us… Two special causes are assigned to this great reaction in public sentiment,—the want of military success, and the impression…that we can have peace with Union if we would… [but that you are] fighting not for Union but for the abolition of slavery.

Lincoln denied that emancipation was his only goal, but also pointed to the 130,000 black soldiers and sailors then fighting for the Union cause: “The promise being made, must be kept…Abandon all the posts now possessed by black men…& we would be compelled to abandon the war in 3 weeks.” He invoked a moral commitment as well:

There have been men who have proposed to me to return to slavery the black warriors of Port Hudson and Olustee. I should be damned in time & in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies, come what will.

Lincoln worried that he had failed to convince the Northern public during the campaign, and that he would be defeated in 1864. His opponent, General George B. McClellan, campaigned on a platform that protected slavery. Only the timing of critical victories by Generals William Sherman in Atlanta and Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley saved Lincoln’s re-election bid.

This Leland-Boker Edition shows Lincoln publicly commemorating his Emancipation Proclamation at a time when disapproval of it threatened his re-election. By offering signed copies to raise money for the Sanitary Commission, Lincoln directly tied the emancipation of slaves to public support for the war effort. This rare document captures the dramatic moment when the nation embraced a new commitment to ending slavery and rededicated itself to the inalienable right of liberty.

Next Page: Lincoln, Slavery, and the Declaration of Independence: Toward Resolution

|