Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

We are not aware of any other example in private hands, and only six institutions list runs that should include this issue.

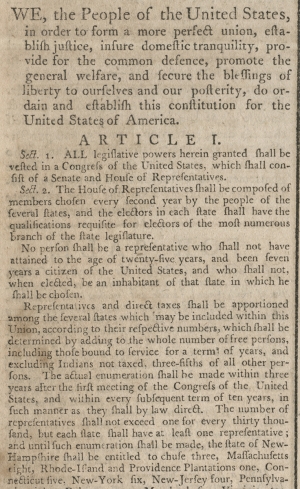

[U.S. Constitution].

The Pennsylvania Herald, Thursday, September 20, 1787. Philadelphia: William Spotswood. Alexander J. Dallas, editor. 4 pp. 11¾ x 19 inches folded, 23½ x 19 inches opened.

Inventory #27499

ON HOLD

Historic Background

On September 17, 1787, after four months filled with contentious debate, the Constitutional Convention completed their work and 39 delegates signed the engrossed Constitution. George Washington, as President of the Convention, also signed two cover Resolutions.

The first resolved that the proposed United States Constitution be “laid before the “United States in Congress assembled,” meeting in New York under the Articles of Confederation. It provided a succinct plan for them to send the Constitution to the states for ratification, and once ratified, to implement the new Federal government by electing representatives, convening Congress, and electing the first president. The second was a transmittal letter to the Confederation Congress.

Hoping to avoid Congress and the states relitigating every hard-fought issue, Washington and the Convention acknowledged that every state, if considering their interests alone, would disagree on certain points, but that compromise was necessary for the greater good of all.

“It is obviously impracticable in the federal government of these states, to secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each, and yet provide for the interest and safety of all: Individuals entering into society, must give up a share of liberty to preserve the rest… It is at all times difficult to draw with precision the line between those rights which must be surrendered, and those which may be reserved... the several states as to their situation, extent, habits, and particular interests.

In all our deliberations on this subject we kept steadily in our view, that which appears to us the greatest interest of every true American, the consolidation of our Union, in which is involved our prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence. This… led each state in the Convention to be less rigid on points of inferior magnitude, than might have been otherwise expected; and thus the Constitution, which we now present, is the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensible.

That it will meet the full and entire approbation of every state is not perhaps to be expected; but… that it is liable to as few exceptions as could reasonably have been expected, we hope and believe; that it may promote the lasting welfare of that country so dear to us all, and secure her freedom and happiness, is our most ardent wish.”

The Constitution was immediately sent to printers Dunlap & Claypoole. By Tuesday, September 18th, up to 500 copies (200 is more likely) were printed for distribution to and by the delegates. That morning, William Jackson, Secretary to the Convention, set out on the 10 am stagecoach to deliver the results to the Articles of Association Congress in New York.

That same morning, the Constitution was first publicly read to the Pennsylvania General Assembly. The next day, September 19, five Philadelphia newspapers published the Constitution. The Pennsylvania Herald was at that point a triweekly that came out on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays; it was the only paper to publish the Constitution on Thursday, September 20th.

Within twenty days, at least fifty-five of the approximately eighty American newspapers of the period had printed the Constitution. (Rapport, “Printing the Constitution,”p.89). Thanks to a free press, the great debate on its ratification would begin, officially starting after Congress re-printed it in New York on September 28th, adding its own transmittal to the states.

Original Provenance:subscriber “J. Bloomfield Esq.,” very likely New Jersey Attorney General Joseph Bloomfield (1753-1823), who later served as the state’s governor.

The Pennsylvania Herald, and General Advertiser(1785-1788), was founded by Irish-born Mathew Carey (1760-1839) in January 1785 as Carey’s Pennsylvania Evening Herald. Carey had fled Dublin to avoid prosecution for his anti-British publications, arriving in Philadelphia in November 1784. Learning of his misfortunes, the Marquis de Lafayette gave him $400 to start a newspaper. By March 1785, it had become the Pennsylvania Evening Herald, and the American Monitor, with fellow Irishmen Christopher Talbot and William Spotswood as partners. Carey began attending Pennsylvania’s General Assembly in the summer of 1785, taking down the debates and votes in shorthand. Although newspapers in England had begun to do so, it was novel in the United States, and the circulation of the Herald grew dramatically. At the end of May 1786, the title changed to The Pennsylvania Herald, and General Advertiser. In February 1787, the partnership dissolved, and Spotswood continued publishing the paper alone. In February 1788, when he retired, Carey again became the publisher.

Alexander James Dallas(1759-1817), who later served as Secretary of the Treasury under James Madison, edited the paper in 1787 and 1788, while simultaneously editing the Columbian Magazine. During Pennsylvania’s ratification debates, Dallas published versions of the debates with his own commentary, which readers considered too Anti-Federalist. Carey fired Dallas, but the Herald lost too many Federalist subscribers to survive; it soon went out of business.

References

Richard Beeman, Stephen Botein & Edward C. Carter II, eds. Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and American National Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987).

Richard B. Bernstein. Are We To Be A Nation? (Harvard University Press, 1987).

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/dube/inde12.htm

Catherine Drinker Bowen. The Story of the Constitutional Convention: May to September 1787 (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1986).

Clarence S. Brigham. History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, Vol. II, pp. 942-944

David Brion Davis & Steven Mintz. The Boisterous Sea of Liberty (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Ann Marie Dube. A Multitude of Amendments, Alterations and Additions (Independence

National Historic Park, May 1996), Appendix H.

Max Farrand. The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966).

Leonard Rapport. “Printing the Constitution: The Convention and Newspaper Imprints, August – November 1787” in Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives. Vol. 2 No. 2, Fall 1970.

Clinton Rossiter. 1787: The Grand Convention (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987).