Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

“Just at the moment I am so angry with that infernal little Cuban republic that I would like to wipe its people off the face of the earth. All we have wanted from them was that they would behave themselves and be prosperous and happy … they have started an utterly unjustifiable and pointless revolution and may get things into such a snarl that we have no alternative save to intervene - which will at once convince the suspicious idiots in South America that we do wish to interfere after all, and perhaps have some land-hunger!...”

This “Confidential” letter brims with significant content, as Roosevelt comments on hunting, disarmament, the Cuban Revolution, and the American voter. He expressed particular frustration at the inability of the new Cuban Republic to maintain a legitimate democracy. In September 1905, candidate Tomás Estrada Palma and his party rigged the Cuban presidential election to ensure his victory over liberal candidate José Miguel Gómez. The liberals revolted in August 1906, leading to the collapse of Estrada Palma’s government the following month, and to U.S. military and political intervention.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT.

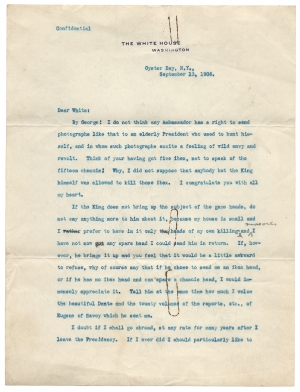

Typed Letter Signed, to Henry White, September 13, 1906, Oyster Bay, New York. Autograph Endorsement as Postscript. On “The White House” letterhead. 3 pp., 8 x 10¼ in.

Inventory #27311

Price: $12,500

Complete Transcript

Confidential

The White House

Washington

Oyster Bay, N.Y.,

September 13, 1906.

Dear White:

By George! I do not think any Ambassador has a right to send photographs like that to an elderly President who used to hunt himself, and in whom such photographs excite a feeling of wild envy and revolt. Think of your having got five ibex, not to speak of the fifteen chamois! Why, I did not suppose that anybody but the King himself was allowed to kill those ibex. I congratulate you with all my heart.

If the King does not bring up the subject of the game heads, do not say anything more to him about it, because my house is small and I prefer to have in it only the heads of my own killing, and moreover I have not now got any spare head I could send him in return. If, however, he brings it up and you feel that it would be a little awkward to refuse, why of course say that if he chose to send me an ibex head, or if he has no ibex head and spare a chamois head, I would immensely appreciate it. Tell him at the same time how much I value the beautiful Dante and the twenty volumes of the reports, etc., of Eugene of Savoy which he sent me.

I doubt if I shall go abroad, at any rate for many years after I leave the Presidency. If I ever did I should particularly like to <2> see him. I entirely agree with his position about disarmament. It would be an admirable thing if we could get the nations not to improve their arms. Ask the King if it would not be possible to get them to agree hereafter not to build any ships of more than a certain size. Of course the United States has not any army and it can do nothing to decrease the size of armaments on land; but I will be glad to follow any practical suggestion as to putting a stop to the increase of armaments at sea. I think that the reduction in the size of ships as above outlined would be a practicable, tho a small, step.

In the MacNutt matter I have not a suggestion to make. Do anything that you deem wise under the circumstances and I will be content.[1]

I do wish the Vatican people would have sense enough to get to terms with the King. They ought to, for more than one reason. I am much interested in what you say about the Jesuits and the French Ecclesiastical question.

Root has certainly had a wonderful time and I think he has accomplished real good.[2] Just at the moment I am so angry with that infernal little Cuban republic that I would like to wipe its

people off the face of the earth. All we have wanted from them was that they would behave themselves and be prosperous and happy so that we would not have to interfere. And now, lo and behold, they have started an utterly unjustifiable and pointless revolution and may get things into such <3> a snarl that we have no alternative save to intervene - which will at once convince the suspicious idiots in South America that we do wish to interfere after all, and perhaps have some land-hunger!

Give my warm regards to Mrs. White. I have heard as golden accounts of her as of you.

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt

Hon. Henry White,

The American Ambassador, / Rome.

[Postscript in Roosevelt’s hand:] I think it is a toss up whether we do or do not win in the congressional election; there are many fools, and many good men who do’n’t take the trouble to think deeply—and they all vote.

Historical Background

On August 29, 1906, American Ambassador to Italy Henry White wrote to President Roosevelt that he had recently spent a week with King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy. He spoke specifically on the limitation or reduction of armaments, and the King said it “would be a great boon to the finances of this country, were there a possibility of an international agreement on this question, which he thought might not be difficult in respect to navies. He fears however that it would be practically impossible to ensure the carrying out by the great European military Powers of such an agreement in respect to their armies.”[3] White wrote of the King’s “great admiration for you” and hoped that Roosevelt would visit Italy when he was no longer president.

White also sent “little kodak photographs” of the King and himself hunting ibex and another “which he took of me holding the horns of one of the five ibex that I killed during the week.” He described the hunting trip that he and the King took into the Piedmontese Alps to hunt ibex and chamois. White described the King as “a very level headed man, singularly devoid of prejudices, with plenty of character, decided views on most subjects, simple also in his tastes, and I need scarcely say that on this occasion the trappings of royalty, which he always reduces to a minimum, were entirely absent.”

White noted that King Victor Emmanuel III “was very interesting on the relations of his government with the Vatican. The more I realize how excellent, even if not official, those relations are, the more improper I deem it that the Pope should refuse to receive or have anything to do with the representative of over twenty millions of the most enlightened Roman Catholics, who contribute so largely to the support of the Holy See.” White closed with a hope that the Congressional elections “will go alright this fall, but I suppose we must expect a certain falling off in the Republican majority.”[4]

President Roosevelt responded to White’s letter with this letter expressing his envy of White’s hunting opportunity with the Italian King. The President continued to discuss European disarmament, the relationship between the Kingdom of Italy and the Vatican, the Cuban Revolution, and the upcoming Congressional elections.

King Victor Emmanuel was embittered by the refusal of the Catholic Church to recognize Rome as the capital of Italy. Pope Pius X, who held the Papacy from 1903 until he died in 1914, maintained the “prisoner in the Vatican” stance toward the Kingdom of Italy that persisted with each pope from 1870 to 1929. A series of five popes, of whom Pius X was the third, refused to leave the Vatican to avoid the appearance of accepting the authority over Rome of the Italian government, which they considered illegitimate. Only with the Lateran Treaty of 1929 that created the modern state of Vatican City did this situation end. The Holy See acknowledged Italian sovereignty over the former Papal States, and the Kingdom of Italy recognized the sovereignty of the Pope over the Vatican City microstate.

The Spanish-American War of 1898, in the Cuban theatre of which Rough Rider Teddy Roosevelt played a prominent role, resulted in the Spanish loss of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba. In December 1898, Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris, in which Spain recognized Cuban independence. However, the United States prevented Cuban resistance leaders from participating in the peace talks and the signing of the treaty, and the treaty did not set a time limit on the U.S. occupation of Cuba, which ended in 1902. In 1903, officials from the two countries signed the Cuban-American Treaty of Relations, which allowed the United States to intervene in Cuba “for the preservation of Cuban independence, the maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, property, and individual liberty, and for discharging the obligations with respect to Cuba imposed by the Treaty of Paris on the United States, now to be assumed and undertaken by the Government of Cuba.”

In 1906, both the government of Cuban President Tomás Estrada Palma and his political opponents sought U.S. intervention, but President Roosevelt was reluctant to get involved. When Palma’s government collapsed in September, the United States invoked the terms of the 1903 treaty, and President Roosevelt sent U.S. military forces to Cuba and established the Provisional Government of Cuba on September 29, 1906, with Secretary of War William H. Taft as Provisional Governor of Cuba.

The U.S. military forces were to prevent fighting between the Cubans, protect U.S. economic interests there, and supervise the holding of free elections to establish a new and legitimate government. When José Miguel Gómez was elected in November 1908, U.S. officials determined that Cuba was stable enough to withdraw U.S. troops, which was completed by February 1909. On September 20, 1906, Ambassador White wrote to President Roosevelt that “your prompt and vigorous through conservative action in Cuba meets with universal admiration and approval and from todays news it looks as though you would succeed in setting the Republic on its legs again, for a time at all events. But in any case you have succeeded in dispelling the idea that we want to annex Cuba or any other territory and it is now thoroughly realized in Europe that if we have to interfere to keep the peace in that island it will be with the greatest reluctance.”[5]

Before the 1906 Congressional elections in the middle of Theodore Roosevelt’s second term, the Republicans held 251 seats in the House of Representatives, while the Democrats had only 135 seats. Republicans lost 28 seats and Democrats gained 32 seats in the November 6 election, leaving the Republicans with a 223-to-167 majority in the House. In the U.S. Senate, where thirty seats were contested, Republicans gained three seats, extending their majority to 60 seats, while the Democrats held 29, and 1 seat was vacant.

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) was born in New York City, graduated from Harvard University in 1880, and attended Columbia Law School. He served in the New York State Assembly from 1882 to 1884, and as president of the New York City Police Commissioners in 1895 and 1896, then as Assistant Secretary of the Navy from 1897 to 1898. After service in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, he won election as Governor of New York and served from 1899 to 1900. He ran as Vice President to William McKinley in 1900 and became President in September 1901, when McKinley was assassinated. Reelected in 1904, Roosevelt was President until 1909. A prolific author and naturalist, Roosevelt was instrumental in the Progressive movement of the early twentieth century, helped preserve the nation’s natural resources, and extended American power throughout the world with a focus on a modern navy. In 1912, he again sought the Republican nomination for President, but when the convention chose incumbent William Howard Taft, Roosevelt formed the Progressive Party and outpolled Taft in the general election. The Republican division allowed Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency.

Henry White (1850-1927) was born in Baltimore into a wealthy family whose sympathies were with the Confederacy during the Civil War. After the war, his family moved to France, where White finished his education in Paris. They moved to Great Britain after the fall of Napoleon III during the Franco-Prussian War. There, White became an avid fox hunter, a sport that introduced him to many leading figures of Victorian Britain. In 1879, he married Margaret Stuyvesant Rutherfurd (d. 1916), with whom he had two children. He returned to the United States and in 1883 received an appointment as a secretary to the U.S. legation in Vienna. He soon moved to the U.S. legation in London, where he remained until being removed for political reasons in 1893. He returned to Washington, D.C., where he continued to charm leaders with his social graces. He was appointed to the London embassy in 1896 and remained there until President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him as U.S. ambassador to Italy in March 1905. In December 1906, Roosevelt appointed White as U.S. ambassador to France, where he remained until Taft took office in 1909. In 1910, he accompanied former President Roosevelt on his tour of Europe. Later that year, President Taft appointed White to head the U.S. delegation to the Pan-American Conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina. During World War I, White initially remained neutral because of his strong ties to both Great Britain and Germany. In 1918, he served as one of five American Peace Commissioners to end the war, and he was one of the signers of the Treaty of Versailles. The U.S. Senate’s refusal to ratify the treaty ended White’s diplomatic career. Roosevelt once called White “the most useful man in the entire diplomatic service, during my Presidency and for many years before.”

Victor Emmanuel III (1869-1947) was born in Naples as the son of King Umberto I of Italy. When his father was assassinated in 1900, he acceded to the throne as Victor Emmanuel III. In his early reign, he was committed to constitutional government. Although World War I was largely disastrous for Italy, the King commanded the respect and affection of the majority of Italians. The economic depression after the war led to extremism among Italy’s working classes, allowing Benito Mussolini and the Fascists to come to power in 1922. As Mussolini consolidated power, the King offered no resistance, believing Mussolini was saving Italy from the communists and socialists. He allowed Mussolini to open negotiations with the Vatican in 1926, which resulted in the Lateran Treaty of 1929, settling the “Roman Question.” World War II was disastrous for Italy. After Allied forces invaded Italy and deposed Mussolini, Victor Emmanuel fled to southern Italy and reluctantly switched sides and declared war on Germany in 1943. In 1946, Victor Emmanuel abdicated in favor of his son, who became King Umberto II and had been exercising most of the King’s powers since 1944. Italians abolished the monarchy in June 1946. Victor Emmanuel went into exile in Alexandria, Egypt, where he died in 1947.

Condition: Expected mailing folds; light creasing; minor toning and soiling; a few rusty paper clip impressions; else, near fine condition.

[1] Francis Augustus MacNutt (1863-1927) was born in Indiana, converted to Catholicism, and became an American diplomat in Madrid and Constantinople. As Papal Chamberlain of the Cloak and Sword, he became highly influential in Vatican circles and was a close friend of three successive popes and several cardinals. MacNutt also had considerable influence in the Austrian Imperial Court through his close ties with members of the imperial family, including Empress Zita. He worked to find solution to the “Roman Question” that divided the Kingdom of Italy and the Vatican. In 1905, MacNutt was removed from his position in the Vatican and sentenced to three months imprisonment “with provisory liberty.” In early September 1906, MacNutt wrote to White from Austria about “certain calumnies spread against me in Rome.” He insisted that President Roosevelt had been misled about him and that he had suffered “a great wrong” which only the President could set right. Francis Augustus MacNutt to Henry White, September 3, 1906, Theodore Roosevelt Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[2] Secretary of State Elihu Root (1845-1937) toured several Latin American countries in 1906 and persuaded them to participate in the Hague Peace Conference of 1907, called at the suggestion of President Roosevelt. He also convinced them that American interventions in Central America had been “friendly interventions” on behalf of peace and security.

[3] On August 14, 1906, President Roosevelt had written a confidential letter to White with “tentative and suggestive” observations about limitations or reductions of armaments: “I agree entirely with [British Secretary of War] Haldane that it is very advisable to put a check to the inordinate growth of armaments.” Roosevelt insisted that the United States was in no position to reduce either its “small navy” or “so much smaller as to seem infinitesimal” army. He felt it would be a “great misfortune for the free peoples to disarm and leave the various military despotisms and military barbarisms armed.” He concluded that “we can only accomplish good at all by not trying to accomplish the impossible good.” Theodore Roosevelt to Henry White, August 14, 1906, Theodore Roosevelt Papers, Library of Congress.