Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

“By virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons…”

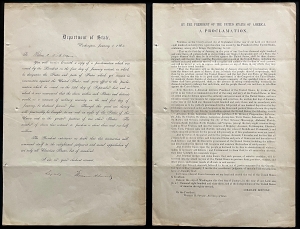

One of the first obtainable printed editions of Abraham Lincoln’s final Emancipation Proclamation, January 1863, issued by the State Department.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

Printed Circular,

“By the President of the United States of America. A Proclamation.” First page: WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Printed Letter Signed by Secretary, to Robert C. Kirk, January 3, 1863. [Washington: Government Printing Office, ca. January 5, 1863], 2 pp. on one folded sheet, 8¼ x 13 in. (pages 2 and 4 blank)

Inventory #27119.99

Price: $115,000

Partial Transcript

[Letter of transmittal:]

Department of State,

Washington, January 3, 1863.

To Robert C. Kirk, Esqr

You will receive herewith a copy of a proclamation which was issued by the President on the first day of January instant, in which he designates the States and parts of States which yet remain in insurrection against the United States, and gives effect to the proclamation which he issued on the 22d day of September last, and in which it was announced that the slaves within such States and districts would, as a measure of military necessity, on the said first day of January, be declared forever free. Through this great act, slavery will practically be brought to an end in eight of the States of this Union and in the greater portions of two other States. The number of slaves thus restored to freedom is about three and one-half millions.

The President entertains no doubt that this transaction will commend itself to the enlightened judgment and moral approbation of not only all Christian States, but of mankind.

I am sir, your obedient servant,

Signed William H. Seward

The second page prints the full text of Lincoln’s final Emancipation Proclamation, signed in type by Lincoln and Seward. This fourth separately printed fourth edition of the final Emancipation Proclamation was preceded only by a virtually unobtainable broadsheet printing, a newspaper broadside by the Illinois State Journal in Springfield, and a nearly identical State Department printing lacking the attached transmittal letter.

Bibliographer Charles Eberstadt describes this edition as “a circular printed for dissemination to the foreign service posts of the Department of State” and hypothesizes that it was printed on or about January 5, 1863, four days after the proclamation was first issued. Eberstadt located only four examples of this imprint, of which only the copy at the National Archives still had the transmittal letter attached—that one to Charles Francis Adams as the American Embassy in London, which Adams received on January 19, 1863.[1] Only one other example has appeared at auction in the past forty years.

Historical Background

By the summer of 1862, President Lincoln believed it was becoming possible and necessary to tear down the chief pillar of the Confederacy. He intended to issue the proclamation in June, but his cabinet counseled waiting until after a Union victory lest it be seen as an act of desperation. The Battle of Antietam provided an opportunity, and on September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, warning Southern states to abandon the war or face losing their slaves in 100 days.

The text of this (final) Proclamation reveals the major themes of the Civil War: the importance of slavery to the war effort on both sides; the courting of border states; Lincoln’s hopes that the rebellious states could be convinced to come back into the Union; the role of black soldiers; constitutional and popular constraints on emancipation; the future place of African Americans in society, and America’s place in the worldwide movement towards abolition.

Anti-abolition and racist sentiment was widely shared in the North and throughout the army, so signing the Proclamation carried considerable risk as Union hold on the five slave states that had remained loyal (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and West Virginia) was tenuous at best. Lincoln reportedly said that while he hoped to have God on his side, he must have Kentucky. Thus, he tailored his proclamation as narrowly as possible to help it survive constitutional challenge in unfriendly courts, and focused on the military necessity of attacking slavery, a key resource of the Confederacy. Despite officially operating only in territory controlled by the Confederacy, the Proclamation initially free about 50,000 (including many self-emancipated slaves) with the stroke of his pen.

“And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages….”

This most revolutionary part of the document is often overlooked. Rather than hearing Lincoln patronizingly telling freed slaves to behave themselves, we read this as an announcement to whites that black men and women who were treated as chattel now could legally act in self-defense. This is squarely in opposition to the most notorious part of the 1857 Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which deluded pro-slavery forces into thinking that the slavery controversy had been solved. Chief Justice Roger Taney’s majority opinion went so far as to declare that blacks, “regarded as beings of an inferior order,” had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Further, Lincoln knew that freed persons didn’t need to be told to “get a job.” He often spoke of the great injustice of depriving men and woman of the fruit of their own labor. Again, these words were likely aimed not at the freed slaves, but at those who had the power to hire them. Equal pay for equal work is still a challenge 115 years later; “reasonable wages” would have been a revolutionary start.

Demonstrating the evolution of his thinking, the final Proclamation eliminated references to colonization and compensation to slave owners for voluntary emancipation.

A key facet of Lincoln’s genius was his ability to inspire as broadly as possible but act as narrowly as necessary – threading needle after needle before anyone could even begin to see a tapestry. Lincoln also declared that “such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” Ultimately, 200,000 African-Americans fought for the Union. By war’s end, they made up ten percent of the Union army and a higher percent of the navy. We see this as an attempt to make the necessity of recruiting and arming black soldiers sound as unthreatening as possible.

Robert C. Kirk (1821-1898) was born in Ohio and attended Franklin College in New Athens, Ohio, but did not graduate. He studied medicine and began a medical practice in Illinois. He later opened a dry goods store in Mount Vernon, Ohio, where he sold his own special-recipe elixir. He was elected to the Ohio Senate as a Democrat in 1855, but his commitment to abolitionism led him to join the newly forming Republican party. In 1859, he was elected lieutenant governor on a ticket with gubernatorial candidate William Dennison. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Kirk as the U.S. Minister Resident to the Argentine Republic. He became a friend of Argentine President Bartolomé Mitre and arranged for the repayment of old Argentine debts. When Andrew Johnson succeeded Lincoln, Kirk was either dismissed or voluntarily left his post in 1866. President Ulysses S. Grant reappointed Kirk in 1869 as the Minister to Argentina and Uruguay. When another diplomat was appointed as Minister to Uruguay in 1870, an offended Kirk resigned in 1871 and returned to Ohio.

Condition: Stab holes in left margin, not affecting text; three light horizontal folds; a few minor chips; small amount of dampstaining and foxing in margins.

[1] Charles Eberstadt, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (NY: Duschnes Crawford, Inc., 1950), 18 (No. 11).