|

An Evolving Stance on Emancipation |

Lincoln had always believed slavery to be immoral, and fought its expansion. At the same time, he recognized that the president did not possess the Constitutional power to abolish the institution. As Lincoln’s paramount aim was to restore the Union, he had reason to be cautious. He saw that anti-abolition sentiment was widely shared in large parts of the North, and throughout the army. He also recognized that the Union’s hold on the five slave states that had remained loyal (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and West Virginia) was tenuous at best, and that maintaining it was absolutely critical.

|

|

|

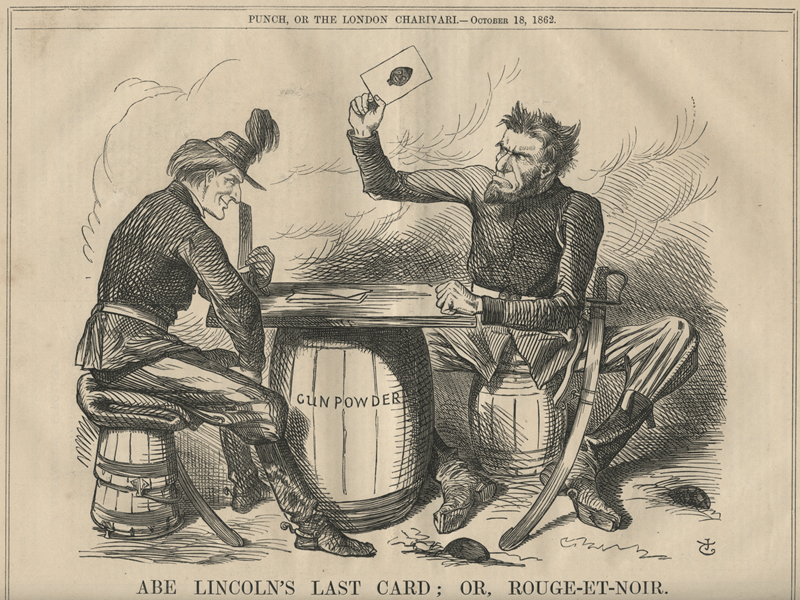

Lincoln plays the race card, engraving by John Tenniel, Punch, October 18, 1862. |

In a message to Congress on July 4, 1861, Lincoln stated that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the States where it exists.” When Generals John C. Frémont, in August 1861, and David Hunter, in May 1862, issued their own emancipation orders, Lincoln was forced to rescind them. His approach was more incremental. In March 1862, Lincoln supported the Confiscation Act, which was not intended to end slavery but did free slaves in rebellious states as “contrabands” or “captives of war” who would not be returned to “claimants.” He also proposed “Compensated Emancipation,” offering to pay slave owners and give them time to adjust to a free labor society, noting that the cost of buying freedom for all slaves would be less than the cost of prosecuting the war. Soon after, Lincoln began to describe slaves as an economic and military “element of strength to those who had their service.” He told his advisers, “We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued.” Freeing slaves was becoming, in historian James McPherson’s words, “a means to victory.”

|

|

|

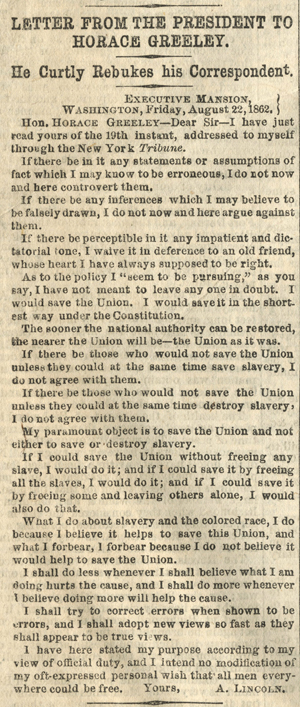

Lincoln’s response to Greeley’s “Prayer of Twenty Millions,” Philadelphia Enquirer, August 25, 1862. |

Major Thomas Thompson Eckert, the chief of the War Department’s telegraph office, was the first to see the president quietly turn the full force of his intellect on the problem of slavery. Lincoln often sat in Eckert’s office, waiting, head in hands, for telegraphed news of battles. In the first week of July 1862, Lincoln asked Eckert for some paper, “as he wanted to write something special.” Seating himself at Eckert’s desk, he began to write what has been regarded as the first draft of the Proclamation. Eckert later recalled that Lincoln would look out of the window a while and then put his pen to paper, though never writing much at once. After a period of study, he would make up his mind and put down a line or two, then sit for a few minutes to contemplate the next move. Lincoln returned to Eckert’s office almost daily over the next few weeks. By the end, Eckert had become “impressed with the idea that he [Lincoln] was engaged upon something of great importance.” When Lincoln finished, he told Eckert that he had been “writing an order giving freedom to the slaves in the South. He said he had been able to work at my desk more quietly and command his thoughts better than at the White House, where he was frequently interrupted.”

To overcome Constitutional objections, Lincoln wrote the Proclamation as Commander in Chief. He carefully crafted it as a war measure, going so far as to exempt not just the border states, but all areas formerly in the Confederacy that had been taken back into the Union.

In August, New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley assailed Lincoln in print for not doing enough to end slavery. Lincoln’s response demonstrated a keen awareness of the Constitutional tightrope he had been forced to walk:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I don't believe it would help to save the Union.... I have here stated my purpose according to my view of Official duty: and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

With an Emancipation Proclamation secretly drafted already, Lincoln’s response could be considered disingenuous. He was ready to lay the groundwork for emancipation, but he feared that delivering the Proclamation at the wrong time would doom its chances for public acceptance and harm the Union cause. Emancipation threatened one of his most crucial goals in the first half of the war: maintaining the support of the slaveholding border states that remained in the Union. Lincoln reportedly said that while he hoped to have God on his side, he must have Kentucky.

|

|

|

The First Reading of the Emanacipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet. Painted by F.B. Carpenter, Engraved by A.H. Ritchie, 1866. |

Lincoln read an early draft of the proposed Proclamation to his Cabinet in July 1862. Secretary of State William Seward, fearing it would be considered a desperate move, advised the president to wait for a Union victory before issuing the order. Two months later, when Union troops stopped Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland at Antietam Creek, Lincoln finally had his opportunity.

|

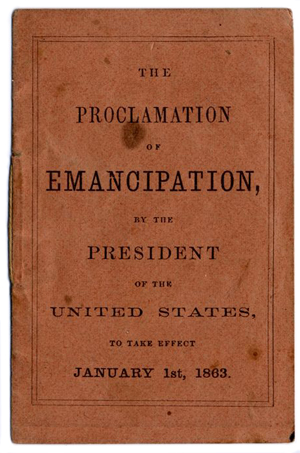

Miniature printing of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation,

William Forbes, 1862. |

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, giving the South 100 days to end the rebellion or face losing their slaves. On both sides of the Mason-Dixon line, Lincoln’s order was condemned as a usurpation of property rights and an effort to start racial warfare. But its supporters had a voice as well. In December, John Murray Forbes, a Boston industrialist and abolitionist who had helped raise troops, including the famous African-American 54th Massachusetts regiment, printed a miniature booklet (just over 2 x 3 inches) to distribute throughout the North, and to blacks in the South via Union troops.

As he had promised, the president carefully worded the final document to affect only those states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863:

I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion...do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated states and parts of states are, and henceforward shall be, free; and that the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons. ... And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

His final Proclamation showing Lincoln’s own progression, eliminated earlier references to colonizing freed blacks and compensating slave owners for voluntary emancipation. It also added provisions for black military enlistment. Pausing before he signed the final Proclamation, Lincoln reportedly said: “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper.”

Next Page: The Myth of Non-Emancipation

|