|

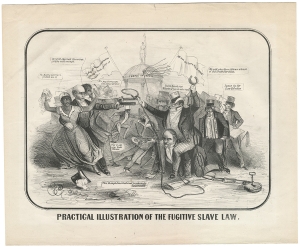

Bold Cartoon on Fugitive Slave Law |

Click to enlarge:

This political cartoon vividly illustrates the conflicts over the operation of the strengthened Fugitive Slave Law, passed by Congress as part of the Compromise of 1850. At the left, an African-American woman cries, “Oh Massa Garrison, protect me!!!” Beside her stand abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, armed with pistols. Garrison reassures her, “Do’nt be alarmed Susanna you’re safe enough.” At center right, a figure representing the slave interests rides atop Daniel Webster, a chief architect of the Compromise, who is down on his hands and knees. The figure says, “Do’nt back out Webster, if you do we’re ruin’d,” and Webster, clutching the Constitution, responds, “This, though Constitutional, is extremely disagreeable.” Another proslavery figure carries large volumes labeled “Law & Gospel” and declares, “We will give these fellows a touch of Old South Carolina,” while another says, “I goes in for Law & Order.” In the background, from the “Temple of Liberty” wave two flags with the inscriptions, “A day, an hour, of virtuous Liberty, is worth an age of Servitude” and “All men are born free & equal.”

The artist "E.C." is possibly Edward Williams Clay, but cataloging at the Library of Congress concludes that “the signature, the expressive animation of the figures, and especially the political viewpoint are, however, uncharacteristic of Clay.”

[Slavery].

E. C. [possibly Edward Williams Clay], “Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law,” Political Cartoon, 1851. 1 p., 15 x 11½ in.

Inventory #27427

Price: $4,500

Historical Background

The United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850. It was one of the most controversial parts of the Compromise because it required that every escaped slave, when captured, had to be returned to the slave’s owner, and officials and citizens of the free states had to cooperate in the process.

The United States Supreme Court had ruled in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) that states did not have to aid in hunting or recapturing fugitive slaves, which significantly weakened the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Some northern states also passed personal liberty laws, requiring a trial before a jury before alleged fugitives could be removed from the state and sometimes prohibiting the assistance of state officials or local jails in the process.

The new act penalized officials who refused to arrest someone allegedly escaping from slavery, and commissioners who decided the fate of the alleged fugitive received $10 if they determined the fugitive was a slave but $5 if they did not. It also subjected citizens who aided fugitive slaves to fines and imprisonment.

The law forced many northerners to consider their attitude toward slavery and their enforced support of it. It helped to galvanize northern sentiment against slavery and prompted Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) in response to the law.

U.S. Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts strongly supported the law as part of the Compromise of 1850, and his support permanently damaged his reputation in Boston, where abolitionists were perhaps stronger than anywhere else in the nation, and throughout New England. In the summer of 1850, he joined the administration of President Millard Fillmore as Secretary of State after President Zachary Taylor’s death. After an unsuccessful campaign for the 1852 Whig nomination for president, Webster retired to his estate and died in October 1852 after a fall from a carriage.

Edward Williams Clay (1799-1857) was born in Philadelphia and attended law school but also worked as an engraver. He left his law career to become a full-time artist. From 1825 to 1828, he studied art in Europe. Between 1828 and 1830, he drew and published Life in Philadelphia, a racist work depicting early African American life in Philadelphia. Beginning in 1831, he focused on political cartoons and relocated to New York City in 1837, where he often worked with print publisher Henry R. Robinson (1785-1850) to develop an informal support system for political caricature. Clay’s deteriorating eyesight forced him to retire as an artist in 1852, and he moved to Delaware, where he served as clerk of the Court of Chancery and the Orphan’s Court. He died in New York City of tuberculosis.