Click to enlarge:

Select an image:

“I will go into Office totally free from pre-engagements of every nature whatsoever, and in recommendations to appointments will make justice & the public good, my sole objects.”

The still unofficial President-elect George Washington writes in March 1789 about his determination to go into the presidency with no pre-existing commitments, ready to purely judge the“justice & the public good” of every appointment. He would extend that sentiment to every aspect of his presidency.

Washington referred to the standard of “justice & the public good” only a few times, and the present letter is the only example we know of that has ever reached the market.

GEORGE WASHINGTON.

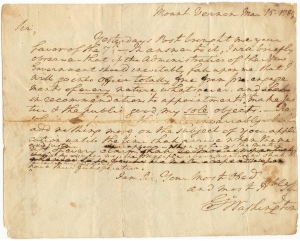

Autograph Letter Signed, to Frederick Phile, March 15, 1789, Mount Vernon, Virginia. Washington’s retained copy, written on blank leaf of Phile’s letter to him as evidenced by partial address on verso: “[George]

Washington / [Moun]

t Vernon.” 1 p., 8 x 6¼ in.

Inventory #27734

Price: $550,000

Complete Transcript

Mount Vernon Mar 15th 1789

Sir,

Yesterdays Post brought me your favor of the 7th – In answer to it, I will briefly observe that if the Administration of the New Government should inevitably fall upon me that I will go into Office totally free from pre-engagements of every nature whatsoever, and shall in recommendations to appointments ^will^ make justice & the public good, my sole objects. Resolving to pursue this rule, invariably –I shall[1] add nothing more on the subject of your application until the time shall arrive when the merits ^and justice^ of every claimt shall be most [?]actually attended to so far as the matter depends upon ^[?] appear – when, so far as the matter shall depends upon me, the principles above mentioned shall to the best of my judgment^ have their full operation.

I am Sir, Your Most Obedt

and most Hble Ser.

Go Washington

[File Note on verso in Washington’s hand:]

To Doctr Fred: Phile / 15th Mar. 1789

See related George Washington Inaugural Address Collection here.

Historical Background

On June 21, 1788, the United States Constitution became the official framework for the government of the United States when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify it. Four days later, Virginia ratified it, and a month later, New York became the eleventh state to ratify the Constitution.[2]

Between mid-December 1788 and mid-January 1789,[3] either by popular vote or by the state legislature, ten states chose a combined total of seventy-three electors.[4] On February 4, sixty-nine of those electors cast two ballots each in their states for the President and Vice President of the United States. The legislatures counted the votes and sent their tallies to the new federal Congress, which was expected to convene at Federal Hall in New York on March 4, 1789. Although both houses initially convened on that date, the House of Representatives did not achieve a quorum until April 1, and the Senate did not reach a quorum and organize itself until April 6. Later that day, the Senate, in the presence of the House, counted the electoral votes. Each of the sixty-nine present electors gave one vote to George Washington, making his election to the presidency unanimous. Thirty-four electors voted for John Adams, thereby selecting him as Vice President.[5]The Senate appointed Secretary of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and keeper of the Great Seal of the United States Charles Thomson to notify George Washington of his election as President.

Well before the official counting, Washington had received reports from various sources making it clear that his election was a virtual certainty, and Washington began making preparations. Charles Thomson traveled to Virginia with official notice of Washington’s election, arriving at Mount Vernon on April 14. Two days later, Washington left Mount Vernon for New York City, the temporary capital of the fledgling nation. Thomson accompanied him on the return journey. Washington arrived in New York City amid great fanfare on April 23 and was sworn in as president on April 30 at Federal Hall.

Frederick Phile wrote to George Washington from Philadelphia on March 7, 1789. After first flattering Washington—“the United Suffrages of confederated America, have named you as President under the new Constitution, and I have no doubt your known Attachment to your Country, will make you obey its calls, and that you will accept of this important Office”—Phile pointed out that as President, Washington would be appointing collectors and naval officers at various ports and got directly to the point of his letter: “I therefore presume to solicit your Excellency to be pleased to nominate me as Naval Officer for the Port of Philadelphia, which Office I have filled (I flatter myself with reputation) either as a Deputy, or Principal, upwards of thirty five Years.” He continued with the details of his service and his current duties and closed with a request for Washington’s forgiveness for “my troubling you with so long a letter on this Subject.”[6]

In Philadelphia, there seemed to be a rumor that Phile was unfit for a federal position because of habitual drunkenness. Letters of support from Rev. Henry Helmuth, Congressman Daniel Hiester, and U.S. Senator Richard Henry Lee all refuted the charge. Helmuth wrote, “Doctor Phile is almost my nearest Neighbour and I can with a good Conscience testifie that I never have found him in the least given to strong Licquor and am afraid this injurious Report has lately been raised by some people through selfish Views—He has formerly practised Physick but by being placed in the Office he now wishes to retain, he has entirely lost his former Practise, He has a large Family and at the same time the Misfortune of having a Daughter who is entirely deprived of her sight, which would heighten the Misery of a much esteemed and beloved family if he should lose his office.” Lee even began his letter with the line, “I should be wanting both to public and to private justice if I were to omit giving you the information that I have received concerning the charge brought against Doctr Phile late Naval Officer for the Port of Philadelphia.” He continued to explain that he had been informed by several correspondents that the charge against Phile was “a gross falsehood” and “an infamous slander.” Lee believed that Washington was “much too well acquainted with human nature” not to understand that “the right discharge of a man’s duty where it produces hurt to wrong-doers, seldom fails to excite rancorous and violent opposition to the person who does his duty.” [7]

Washington referred to the standard of “justice & the public good” only a few times, and the present letter is the only example we know of that has ever reached the market.

Washington used a similar “public good” expression in a March 9, 1789, letter to Declaration-signer Benjamin Harrison, the father of future president William Henry Harrison and the grandfather of future president Benjamin Harrison. Washington wrote, “if it should be my inevitable fate to administer the government (for Heaven knows that no event can be less desired by me; and that no earthly consideration short of so general a call, together with a desire to reconcile contending parties as far as in me layes, could again bring me into public life) I will go to the chair under no preengagement of any kind or nature whatsoever. But when in it, I will, to the best of my Judg[m]ent, discharge the duties of the office with that impartiality and zeal for the public good, which ought never to suffer connections of blood or friendship to intermingle, so as to have the least sway on decision[s] of a public nature.”[8]

Just a few days later, on March 13, 1789, Washington wrote similarly, telling Declaration signer Francis Hopkinson of New Jersey that he would act “with a sole reference to justice & the public good.”[9]

Washington kept to his word, eventually appointing Phile, not because he had lost his practice or supported a blind daughter but based on many recommendations including that of yet another signer of the Declaration of Independence, Richard Henry Lee. “Justice and the public good” prevailed.

Frederick Phile (ca. 1736/1740–1793) was variously described as “German-born” or born in Baltimore, Maryland. He became a physician in Philadelphia and from the mid-1750s, he also served as deputy naval officer for the port of Philadelphia. In 1760, he married Elizabeth Parrish (1740-1834), and they had ten children. In 1768, he became a close friend of and physician for German-born French General Baron Johann de Kalb (1721-1780), whom he met when de Kalb was visiting Pennsylvania on a covert mission for the French government. Phile served as surgeon of the 5th Pennsylvania Regiment from 1776 to 1777, and when the British occupied Philadelphia (September 1777–June 1778), Phile and his family fled to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Phile served as the naval officer for the port of Philadelphia from 1777 to 1789 under the state government. In August 1789, President George Washington appointed him as the naval officer for Philadelphia under the federal government, a position he held until his death. He died in the yellow fever epidemic in mid-October 1793.

Condition: Minor flaws and some reinforced strips on verso.

[1]This word is “can” in Letterbook 22, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[2]By the spring of 1789, when the First Federal Congress assembled in New York, neither North Carolina nor Rhode Island had ratified the Constitution. After Congress proposed and sent twelve amendments to the states (ten of which became the Bill of Rights) in September 1789, North Carolina ratified the Constitution in November, offering suggested amendments of its own. Rhode Island did not ratify the Constitution until May 29, 1790.

[3]Americans observed the first uniform election day on November 4, 1845, and first voted on the same day for President on November 7, 1848. From 1788 to 1844, presidential elections typically occurred over the course of a month or more.

[4]Out of a possible 91 electors, neither North Carolina (7 electors) nor Rhode Island (3 electors) had yet ratified the Constitution, and the legislature of New York (8 electors) was deadlocked and failed to appoint electors. Two electors from Maryland and one from Virginia neglected to vote. Another elector from Virginia was not chosen because an election district failed to submit its returns.

[5]Electors scattered their second votes among ten other candidates, with only John Jay of New York (9 votes) and John Hancock of Massachusetts (4 votes) receiving votes from more than one state. Other candidates included Robert H. Harrison of Maryland (6), John Rutledge of South Carolina (6), George Clinton of New York (3), Samuel Huntington of Connecticut (2), John Milton of Georgia (2), James Armstrong of Georgia (1), Benjamin Lincoln of Massachusetts (1), and Edward Telfair of Georgia (1).

[7]Henry Helmuth to Washington, July 29, 1789, Daniel Hiester to Washington, July 30, 1789, and Richard Henry Lee to Washington, August 1, 1789, all in George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

[9]Washington to Francis Hopkinson, March 13, 1789, original in National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg; copies in Letterbook, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, and Record Group 59, Miscellaneous Letters, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

For additional references to the standard of “justice and the public good,” see Washington to Benjamin Fishbourn, December 23, 1788, Letterbook, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, and Papers of the Continental Congress, Item 59, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Washington to Samuel Meredith, March 5, 1789, Letterbook, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, and Record Group 59, Miscellaneous Letters, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Washington to Benjamin Lincoln, March 11, 1789, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; George Washington to Gustavus Scott, March 21, 1789, Letterbook, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, and Record Group 59, Miscellaneous Letters, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; and George Washington to Samuel Vaughan, March 21, 1789, Letterbook, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, and Record Group 59, Miscellaneous Letters, National Archives, Washington, D.C.