|

The 15th Amendment, Guaranteeing the Freedmen the Right to Vote, Passes the Georgia General Assembly |

Click to enlarge:

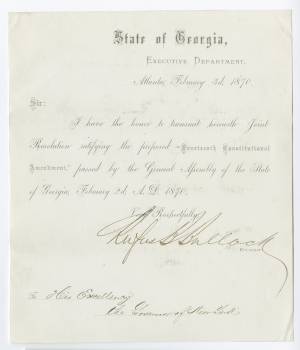

Governor Rufus Bullock, a native New Yorker, informs the governor of his native state that his adopted state has ratified the 15th Amendment, shortly after New York rescinded its earlier ratification.

“I have the honor to transmit herewith Joint Resolution ratifying the proposed ‘Fourteenth (sic) Constitutional Amendment’ passed by the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, February 2d, A.D. 1870.”

It is ironic that this printed letter incorrectly references the “proposed Fourteenth” amendment. Like all other Confederates states except Tennessee, Georgia had initially rejected the Fourteenth Amendment in 1866, just months after President Johnson sent it to the states for consideration. The recalcitrance of southern states led Congress to impose military governments and to require former Confederate states to ratify the Amendment before they could be represented in Congress. Georgia ratified the Fourteenth Amendment on July 21, 1868, providing the final necessary vote for the amendment to go into effect. This letter clearly refers to the Fifteenth Amendment, under consideration by the states in 1869 and 1870.

RUFUS BROWN BULLOCK.

Printed Letter Signed, as Governor of Georgia, to the Governor of New York, February 3, 1870, Atlanta, Georgia. 1 p.

Inventory #22489

SOLD — please inquire about other items

Historical Background

By 1868, the United States Congress had passed, and the required number of states had ratified amendments to the Constitution to abolish slavery and to provide citizenship and equal protection under the laws to the freed people. The 1868 election of Ulysses S. Grant to the Presidency convinced Republicans in Congress that protecting the franchise of African-American men was important for the future of the party.

On February 26, 1869, Congress passed a brief amendment declaring that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude” and providing Congress the power to enforce the amendment.

Because the amendment process required the concurrence of three-quarters of the states, twenty-eight of the thirty-seven states needed to ratify the proposed amendment. Nevada, and most New England and Midwestern states soon did so. Those southern states still controlled by Radical reconstruction governments, like North Carolina, also ratified it quickly. By the summer of 1869, seventeen states had ratified the amendment. Three more states ratified in the fall of 1869, and in January 1870, six more states ratified the proposed amendment, but New York, which had ratified in April 1869, rescinded its ratification on January 5. On February 2, 1870, the Georgia General Assembly ratified the amendment by a joint resolution. The following day, Governor Rufus B. Bullock sent this letter to New York Governor John T. Hoffman, informing him of Georgia’s action. Georgia became the 27th state to ratify, and on the day of this letter, Iowa also ratified. The question of whether New York could legally rescind its ratification became moot, when Nebraska and Texas both ratified the amendment later in February. On March 30, 1870, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish certified the amendment as part of the U.S. Constitution. New York “re-ratified” the amendment that same day.

As in the case of the 13th and 14th Amendments, Congress insisted that former Confederate states that had not returned to full representation ratify the 15th Amendment as well. In 1869, Congress passed Reconstruction bills requiring Virginia, Mississippi, Texas, and Georgia to ratify the amendment before regaining Congressional representation; all four states complied between October 1869 and February 1870. While granting the right to vote in theory, many states obstructed the provisions of the 15th Amendment through poll taxes and literacy tests. It would take nearly a century for the Reconstruction Amendments to be applied fully to all citizens.

In the mid-twentieth century, southern lawmakers attempted to overturn the 14th and 15th Amendments during the early years of the Civil Rights movement. White segregationists in the South were particularly troubled by the U.S. Supreme Court’s use of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment in cases such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In March 1957, the Georgia Senate unanimously adopted as a resolution a memorial to Congress declaring that the 39th and 40th Congresses were “without lawful power to propose any amendment whatsoever to the Constitution” because they excluded duly elected senators and representatives from southern states. Therefore, the 14th and 15th Amendments, passed by those Congresses and sent to the states were “null and void and of no effect from the beginning.” Furthermore, after Georgia and other former Confederate states had rejected the 14th Amendment, Congress, “in flagrant disregard of the United States Constitution,” set up “military occupation or puppet State governments, which compliantly ratified the invalid proposals.” The Georgia legislature called on Congress to declare the 14th and 15th Amendments “null and void and of no effect.”

Rufus Brown Bullock (1834-1907) was born in New York and moved to Augusta, Georgia, in 1857 as part of his job with a telegraph company. During the Civil War, although he opposed secession, Bullock managed railroad and telegraph lines for the Confederacy. He served as president of the Macon and Augusta Railroad in 1867. He was elected Governor of Georgia in 1868 by defeating former Confederate General (and future head of the Ku Klux Klan) John B. Gordon. He was the first Republican governor of Georgia, and his appeal to Congress led to Georgia’s being placed under military rule in December 1869. As a supporter of the Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution, white southerners vilified him as a carpetbagger. His northern business connections brought substantial economic development to his adopted state. Under charges of corruption and pressure from the Ku Klux Klan, Bullock resigned in October 1871 and fled to New York after a “Lost Cause” campaign returned a Democratic majority to the Georgia legislature. After the Republican State Senate president served out the remaining two months of Bullock’s term, no Republican served as governor of Georgia until 2003. Bullock was arrested and returned to Georgia in 1876 to stand trial for embezzlement charges. He was acquitted due to lack of evidence and remained in Atlanta to become one of its most prominent citizens. He left Georgia in 1903 and returned to New York.

John T. Hoffman (1828-1888) was born in New York and graduated from Union College in 1846. He studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1849, when he opened a practice in Manhattan. He became active with the Tammany Hall faction of the Democratic Party and served as Mayor of New York City from 1865 to 1868. Harper’s Weekly describe him as a “citizen of unblemished reputation” when he was elected Mayor. In 1868, he was elected Governor of New York and served from January 1869 to December 1872. Hoffman’s gubernatorial career was eventually destroyed by unfounded accusations of his membership in the notoriously corrupt Tweed Ring.

Condition

Fine

Special Note

The New York State Archive has no correspondence or other files of Governor John T. Hoffman. Most of their gubernatorial correspondence begins in 1883, but they do have a series of official communications between 1859 and 1938. Unfortunately, there is a large gap between 1865 and 1875, the time of Hoffman’s administration.