|

Abolishing Slavery: The Thirteenth Amendment Signed by Abraham Lincoln |

|

The copy of the Thirteenth Amendment described here is the Schuyler Colfax copy, which we acquired privately for collector David Rubenstein. It is one of about fourteen manuscripts Lincoln signed in addition to the original. This copy is significant because it is directly traceable to a leader instrumental in the amendment’s passage. Also included is background information and a census of all the known manuscript copies.

Six Lincoln-signed copies of the Thirteenth Amendment have sold in the last 48 years. I have had the privilege of acquiring and placing all six with institutional and private clients.

I am delighted to share the information we have gathered on this historic document.

Please ask if you wish to re-publish or broadcast any of this information; permission is almost always granted. Free use is granted for non-profit educational purposes, provided that Seth Kaller, Inc. is credited, along with a link to our website.

I am always interested in updating the census (the list of known copies). If you know about a copy not listed here, or if you own a related document, please let me know.

Sincerely, Seth Kaller

|

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude…shall exist within the United States”

|

|

|

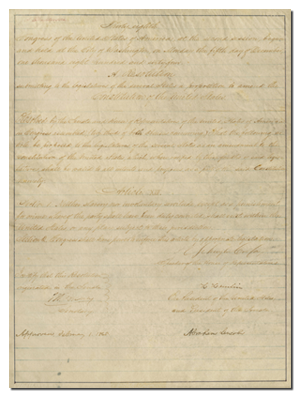

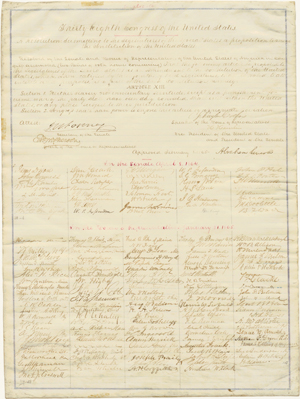

The Colfax copy of the Thirteenth Amendment. |

ABRAHAM LINCOLN. Manuscript Document Signed (“Abraham Lincoln”) as President, with his Autograph Endorsement (“Approved. February 1, 1865.”) Washington, D.C., ca. February 1, 1865. Co-signed by Hannibal Hamlin as Vice President of the United States and President of the Senate, Schuyler Colfax as Speaker of the House, and John W. Forney as Secretary of the Senate. 1 page, 15 1/16 x 20 inches, on lined vellum with ruled borders.

This amendment, outlawing slavery and involuntary servitude, was the first substantive change to America’s conception of its liberties since the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791. After signing the original resolution on February 1, Lincoln responded to a serenade, and to questions about the legality of the Emancipation Proclamation and prior efforts to eradicate slavery, by saying that the amendment “is a king’s cure for all the evils. It winds the whole thing up.”

Transcript

A Duplicate.

Thirty-Eighth Congress of the United States of America, at the second session, begun and held at the City of Washington, on Monday the fifth day of December, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-four.

A Resolution

submitting to the legislatures of the several States a proposition to amend the

Constitution of the United States.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, (two-thirds of both Houses concurring,) That the following article be proposed to the legislatures of the several States as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three-fourths of said legislatures, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as a part of the said Constitution, namely:

Article XIII.

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Schuyler Colfax

Speaker of the House of Representatives.

I certify that this Resolution }

originated in the Senate. } H Hamlin

J. W. Forney } Vice President of the United States,

Secretary. } and President of the Senate.

Approved. February 1, 1865. Abraham Lincoln

Dating and Number of Manuscript Copies

|

|

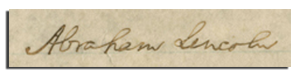

Detail of Lincoln’s signature on the Colfax copy.

|

Having already been approved by the Senate the previous April, the amendment passed in the House on January 31, 1865. The engrossed manuscript was prepared, and Lincoln signed it on February 1st. There does not appear to be any record of the number of “souvenir” copies of the Amendment prepared for Lincoln to sign. Twelve to fifteen are known with Lincoln’s signature. Several additional manuscript copies are known signed by Senators, Congressmen and other officials, but with the space for the President’s name blank. On February 7th, the Senate, anxious not to set a precedent, resolved that the president’s signature had been “unnecessary” on a joint amendment resolution.The Senate secretary, John W. Forney, was directed to “withhold from the House of Representatives the message of the President informing the Senate that he had approved and signed the same....” (Senate Journal) All of the Lincoln-signed copies were likely completed before February 7th. After the resolution, it is probable that the president would have thought it impolitic to sign any additional copies.

See “The Withholding Resolution, From the Journal of the Senate,” for more information.

The “Strohm” Copies of the Amendment

Isaac Strohm was chief engrossing clerk of the House of Representatives during the 38th Congress. In 1896, his daughters sold his signed copy of the Amendment (now at the Huntington Library; the copy most similar to Colfax’s). At the time, they wrote four background letters that have led to the erroneous statement that only three souvenir copies of the Amendment were signed. By their account, the copies were said to have been prepared for Lincoln, Hamlin and Colfax respectively, but we have not seen any evidence that Lincoln would have had a copy made for himself. The Huntington’s copy was said to be Hamlin’s, but its provenance does not support it as such. The Colfax copy, therefore, is the only one with definitive provenance from any of the original leaders who shepherded the Amendment through Congress.

Schuyler Colfax (1823-1885), born in New York City, moved with his family to Indiana when he was an adolescent. Colfax pursued a career in journalism, serving as legislative correspondent for the Indiana State Journal and becoming part-owner of the Whig organ of northern Indiana, theSouth Bend Free Press (renamed the St. Joseph Valley Register in 1845). Colfax was a member of the 1850 state constitutional convention, and four years later was elected as a Republican to Congress, where he served until 1869. An energetic opponent of slavery, Colfax’s speech attacking the Lecompton Legislature in Kansas became the most widely requested Republican campaign document in the 1858 mid-term election. In 1862, following the electoral defeat of Galusha Grow, Colfax was elected Speaker of the House. In that capacity, Colfax announced the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865: “The constitutional majority of two thirds having voted in the affirmative, the Joint Resolution is passed.” Colfax considered February 1, 1865, the day he signed the House resolution, the happiest day of his life. “Fourteen years before, among a mere handful of kindred spirits in the Constitutional Convention of his State, he had said: ‘Wherever, within my sphere, be it narrow or wide, oppression treads its iron heel on human rights, I will raise my voice in earnest protest.’ He had kept his word, and well earned his share in the triumph.” (Hollister, 245). Colfax next served as Vice President under Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1873). He lost a re-nomination bid in 1872 as a result of his involvement in the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal. [Hollister, Ovando James. Life of Schuyler Colfax (1886).]

|

|

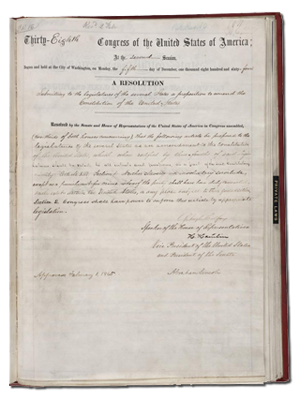

Official copy of the Thirteenth Amendment, now in the National Archives. |

Hannibal Hamlin (1809-1891) had served in the Maine state legislature before entering Congress in 1843 as a Democrat. In 1848 Hamlin was elected by the anti-slavery wing of the Democratic party to fill a vacancy in the Senate. Re-elected in 1850, he served until 1857, at which point he resigned to become the Republican governor of Maine. Hamlin returned to the Senate later that year. Hamlin was chosen as Lincoln’s 1860 running mate in order to “nationalize” the Republican party. Though the nomination stunned Hamlin, he was persuaded that turning it down would only give more ammunition to his former party. Lincoln, a westerner, had been a Whig, and claimed Henry Clay as a political role model. Hamlin, on the other hand, had spent most of his career as a Democrat, and had openly opposed Clay on the Senate floor. What Lincoln and Hamlin shared, however, was their opposition to the expansion of slavery.

In 1864, delegates to the Republican convention did not consider him a strong enough drawing card for voters, especially in border areas or the “reconstructed” south. Instead, Andrew Johnson, the Union military governor of Tennessee, was nominated for the vice presidential slot. As a War Democrat and Southern Unionist, Johnson provided strategic and symbolic power for the Republicans that Hamlin could not. The vice president would later observe that he had been “dragged out of the Senate, against my wishes – tried to do my whole duty, and was then unceremoniously ‘whistled down the wind’” (Hatfield, 203-209). He later accepted a position as collector of the port of Boston, returning to the Senate in 1869. From 1881-82, Hamlin was U.S. minister to Spain, before devoting the remainder of his life to agricultural pursuits.

John Wien Forney (1817-1881), newspaper editor and publisher, was a staunch Democrat whose support for President James Buchanan had brought him government appointments (clerk of the House of Representatives, for instance) and lucrative printing contracts, but not the higher offices to which he aspired. With the decline of his relationship with Buchanan, and his failure to win election to the U.S. Senate over Simon Cameron, he started the anti-Buchanan Philadelphia Press and switched to the Republicans in 1860.

Forney became a key Lincoln supporter. He again served as House clerk and then was appointed secretary of the Senate until 1868. At the same time, he established the Washington Chronicle (which was distributed to the public, and also in large numbers to soldiers in the Army of the Potomac) and maintained his editorial “Letter from Occasional” column in the Press. Forney enjoyed regular White House access, earning him the appellation of “Lincoln’s dog.” He interviewed the President on issues such as freedom of the press and the probable effects of the Emancipation Proclamation, and was invited to consult about cabinet appointments. In 1863, at the consecration of the Gettysburg Cemetery, he got “roaring drunk and gave a violently pro-Lincoln speech” (Boritt). Given this history, perhaps Forney was not suited for another task: He was charged with chaperoning newly-elected vice president Andrew Johnson at the March 4, 1865 inauguration. Johnson was widely criticized for his drunken performance at the ceremony.

After Lincoln’s assassination, Forney continued to support Johnson. But, when Johnson vetoed the Freedman’s Bureau Act in 1868, Forney changed positions and campaigned for Johnson’s impeachment. Selling the Chronicle and returning to Philadelphia, the chameleon-like editor switched back to the Democrats, and started a weekly magazine, The Progress. In addition, he served as a director of the Texas & Pacific Railway.

Click for the Biographical sketches of all the Senators and Congressmen who voted for the Thirteenth Amendment

Abolishing Slavery in all of America

|

|

|

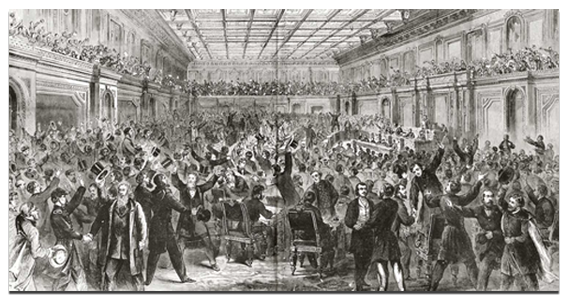

Engraving from Frank Leslie’s magazine of the celebration when the Thirteenth Amendment was passed.

|

While the Emancipation Proclamation was taking its effect in the field, as the Union army advanced, Lincoln also supported Radical Republicans who began to advocate a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery everywhere in the United States. On December 14, 1863, Ohio Congressman James M. Ashley introduced such an amendment in the House of Representatives. Senator John Brooks Henderson of Missouri, a border state that still sanctioned slavery, followed suit on January 11, 1864, courageously submitting a joint resolution for an amendment abolishing slavery.

The proposed amendment passed in the Senate on April 8, 1864, with a vote of 38 to 6. Two months later, however, it was defeated in the House of Representatives, 95 to 66 (or by another account, 93-65), shy of the 2/3 necessary for approval. Lincoln, not about to give up, made abolition a central plank of the National Union platform during his re-election campaign. He argued,

“When the people in revolt, with a hundred days of explicit notice, that they could, within those days, resume their allegiance, without the overthrow of their institution, and that they could not so resume it afterwards, elected to stand out, such [an] amendment of the Constitution as [is] now proposed, became a fitting, and necessary conclusion to the final success of the Union cause. Such alone can meet and cover all cavils…” (Basler, Collected Works, 7, 380).

Lincoln’s victory over McClellan in 1864 gave him a new mandate and enough seats in the House to eventually guarantee passage of the stalled amendment. Not content to wait until the new Congress met in March, the amendment’s supporters brought the measure to another vote in the House on January 31, 1865.

On being informed that the amendment was still two votes short, Lincoln is reported to have told the Republican Congressmen: “I am President of the United States, clothed with great power. The abolition of slavery by Constitutional provisions settles the fate, for all … time, not only of the millions now in bondage, but of unborn millions to come – a measure of such importance that those two votes must be procured. I leave it to you to determine how it shall be done, but remember that I am President of the United States, clothed with immense power, and I expect you to procure those two votes ...” (John B. Alley, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, ed., Rice, 1886 ed., p 585-6. Per Goodwin, p. 687).

The outcome of the vote was in doubt until the final hour. A Pennsylvania Democrat, Archibald McAllister, opened the debate by explaining why he had changed his vote from a “Nay” to an “Aye.” He had been in favor of exhausting all means of conciliation, McAllister stated, but was now satisfied that nothing short of independence would satisfy the Southern Confederacy, and that therefore it must be destroyed, and he must cast his vote against its cornerstone, and declare eternal war with the enemies of the country. Fellow Pennsylvania Democrat Alexander Hamilton Coffroth also changed his vote, and gave a speech advocating passage. Arguments continued until, finally, the votes were tallied. This time it passed, by a vote of 119 to 56, with 8 abstentions. When Speaker Colfax declared the results, “a moment of silence succeeded, and then, from floor and galleries, burst a simultaneous shout of joy and triumph, spontaneous, irrepressible and uncontrollable, swelling and prolonged in one vast volume of reverberating thunder…” (Report of the special committee on the passage by the House of Representatives of the constitutional amendment for the abolition of slavery. January 31st, 1865: The Action of the Union League Club on the Amendment, February 9, 1865, in “From Slavery to Freedom.” American Memory, Library of Congress).

Following in the footsteps of President James Buchanan, who had signed a proposed amendment to protect slavery in the United States, Lincoln signed the official resolution, along with several commemorative copies (fourteen copies with Lincoln’s genuine signature are now known). For that action, the Senate, on February 7th, resolved that the president’s signature had been “unnecessary” and directed the Senate secretary to “withhold from the House of Representatives the message of the President informing the Senate that he had approved and signed the same...” (Senate Journal). It is unlikely that the president would have signed copies of the Thirteenth Amendment resolution subsequent to the “withholding” resolution’s passage.

|

|

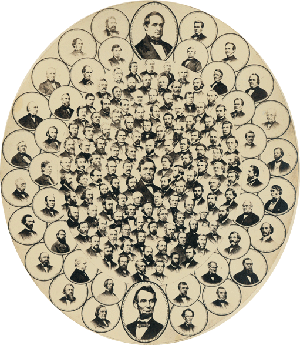

A photographic montage of all the men who made the Thirteenth Amendment, with portraits of President Lincoln (bottom), Vice President Hamlin (top), Speaker of the House Colfax (center), and smaller portraits of members of the House of Representatives and Senators.

|

Despite the celebrations, three-fourths of the state legislatures needed to ratify the amendment before it could be considered part of the Constitution. Accordingly, Secretary of State William H. Seward immediately sent certified copies of the resolution to each governor. In a show of support, Lincoln’s home state of Illinois ratified the 13th amendment on February 1, the same day Lincoln signed the measure. Governor Richard J. Oglesby telegraphed the news to Lincoln at 7:25 that evening, informing him: “[T]he Legislature has by a large majority ratified the amendment to the Constitution. All suppose you had signed the Joint resolution of Congress. Great enthusiasm” (Oglesby to Lincoln, February 1, 1865, AL Papers at the Library of Congress). Five minutes later, Ward H. Lamon, the president’s old law partner, and Edward L. Baker, editor of the Illinois State Journal, relayed the same news. The amendment had passed, they exclaimed triumphantly, “with a great hurrah” (Lamon and Baker to Lincoln, February 1, 1865, AL Papers at the Library of Congress).

Addressing a Washington, D.C. crowd celebrating the historic event, Lincoln offered congratulations on the nation’s great moral victory, but noted that there was still work to be done, state by state. Illinois, he informed them, had already done its part. Maryland was about half through, Lincoln added, but he felt proud that Illinois was “a little ahead” (contemporary newspaper accounts of Lincoln’s speech, Basler 8:255).

By the time General Lee surrendered at Appomattox on April 9, twenty states had ratified the amendment, including Louisiana and Tennessee. Their state governments had already been reconstructed under Lincoln’s so-called “Ten Percent Plan.” On December 8, 1863, Lincoln’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction promised presidential recognition of new state governments once the number of persons swearing allegiance to the United States equaled ten percent of the number of votes cast in that state in the 1860 election.

Tragically, Lincoln did not live to see the amendment become law. He had, by the end of his life, evolved toward a new understanding of the status of black Americans. He now supported giving the vote to literate black men and to black veterans, as he made clear in a speech from a White House balcony on April 11, 1865. On hearing it, John Wilkes Booth angrily told a companion, “That means nigger citizenship. Now, by God, I’ll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make” (McPherson, 852).

On April 14, 1865, when Arkansas became the 21st state to adopt the 13th amendment, only six more states were needed for ratification. That evening, Lincoln was fatally shot by Booth at Ford’s Theatre. Lincoln died the next morning. With Georgia’s ratification on December 6, 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution.

When the amendment went into effect twelve days later, it freed nearly a million slaves still held in bondage. By the end of January 1866, though no longer required for implementation, five more states had added their votes of approval. The remaining states – Texas, Delaware, Kentucky and Mississippi – finally ratified the amendment in 1870, 1901, 1976 and 1995, respectively.

Census of Manuscript Copies of the Thirteenth Amendment Signed by Lincoln

1. National Archives, Washington, D.C. Signed by Abraham Lincoln, Hannibal Hamlin as Vice President and President of the Senate, and Schuyler Colfax as Speaker of the House of Representatives. The official record copy of the resolution of both Houses of Congress effective on January 31, 1865, with its passage by the House. (unique type)

Strohm type (chief engrossing clerk of the House of Representatives)

2. David Rubenstein. The Schuyler Colfax copy. Signed by Lincoln, Hamlin, Colfax, with certification signed by Secretary of the Senate John W. Forney that the resolution originated in the Senate.

3. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Signed by Lincoln, Hamlin, Colfax, with certification signed by Secretary of the Senate John W. Forney that the resolution originated in the Senate.

Variant Senate type

4. University of Delaware, Newark, DE. On the form of the Senate copies, but not signed by Senators, and with a manuscript note above Lincoln’s signature listing the votes in the House and Senate.

Senate type

The following copies are also signed by 36 Senators who voted for the amendment:

5. De Paul Library, St. Mary College, Leavenworth, KS.

6. David M. Rubenstein (ex-GLC).

7. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Indiana State Museum, Indianapolis, IN.

Congressional type

The following copies are also signed by varying combinations of Senators and Representatives:

|

|

An example of the Congressional type. For additional information on this copy click here.

|

8. Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Springfield, IL

9. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

10. The Henry Ford, Dearborn, MI.

11. Gilder Lehrman Collection at The New-York Historical Society, New York, NY. Other than the two Strohm copies, this is the only one that has the signed Forney certification that the resolution originated in the Senate.

12. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

13. Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

14. Private, New York, NY.

15. Private, Greenwich, CT.

Additional copies signed by various officials exist, some of which bear Lincoln’s name but definitely not his actual signature. Examples are in Chicago Historical Society and the Lilly Library.

Related Articles

Historical Background: Slavery and Emancipation in American History

Lincoln, Slavery and the Declaration of Independence: Toward Resolution

References

Basler, Roy P. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln Vol. 5: 442-443, Vol. 7: 394-396

Berlin, Ira. “The Slaves Were the Primary Force Behind Their Emancipation,” in The Civil War: Opposing Viewpoints (San Diego, 1995)

Davis, David Brion and Steven Mintz, eds. The Boisterous Sea of Liberty: A Documentary

History of America from Discovery through the Civil War(New York, 1998)

Eberstadt, Charles. “Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation,” New Colophon (2d Series, 1950) no. 32 (Leland-Boker autographed edition)

Franklin, John Hope. The Emancipation Proclamation (New York, 1963)

Freehling, William W. “The Founding Fathers and Slavery,” in Allen Weinstein et al., eds.,American Negro Slavery: A Modern Reader (New York, 1979)

Goodwin, Doris Kearns.Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Shuster, 2005

Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Horton. In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community and Protest Among Northern Free Blacks, 1700-1860 (New York, 1997)

Kantor, Alvin R. Kantor and Marjorie S. Kantor. Sanitary Fairs: A Philatelic and Historical Study of Civil War Benevolences (Chicago, IL, 1992)

“Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation,” New Colophon (2d Series, 1950) no. 19

McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, 1988)

Peterson, Merrill D. “This Grand Pertinacity”: Abraham Lincoln and the Declaration of

Independence.” Fourteenth Annual R. Gerald McMurtry Lecture, The Lincoln Museum (Fort Wayne, IN, 1991)

Rhodehamel, John, and Seth T. Kaller, “Copies of the Thirteenth Amendment,” Manuscripts, 44, 2 (Spring 1992), p.109, #10.

|